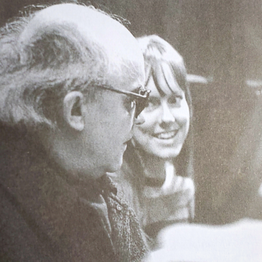

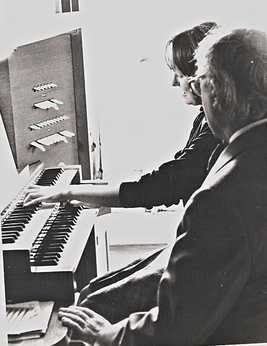

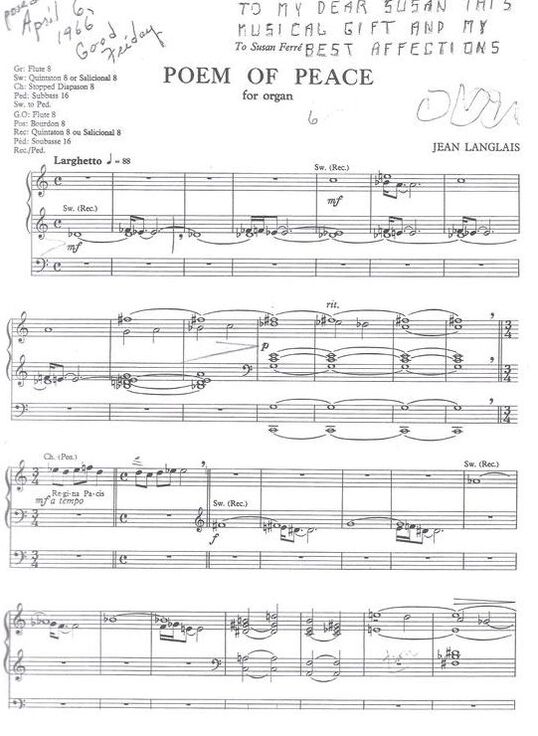

by Susan Ferré How did I end up in Paris, France, during the summer of '64? I had only completed one year of organ study as a Freshman, 18 years old, at Texas Christian U. in Fort Worth, TX. My teacher, Emmet Smith, had previously studied with Rolande Falcinelli, in Paris. Wanting to return to expand horizons, Emmet organized a trip for present and former students, colleagues and friends, to tour the historic organs throughout Europe. An enticement was that we would fly to NYC and from there board the brand new sailing vessel, La France, landing at Le Havre, and from there travel by train during an extensive trip of six weeks. Because I could not afford the trip, but could just barely afford the initial voyage over, an agreement was made with my parents that I would spend the 6 weeks in lessons with Jean Langlais, remaining in Paris in an inexpensive Hotel Dagmar, in the student quarter where meals cost less than a dollar a day, and where I could walk through the Luxembourg Gardens to Ste. Clotilde for lessons twice a week with Maitre Langlais. Practice sessions were also arranged through a music store on Rue de Rennes which rented harmoniums by the hour. The store was located between my hotel in the 5th and my destination, Ste. Clotilde. I would meet my Maitre at the church exactly on time. I was always amazed to see him approaching briskly by himself using only a cane. As I was a beginner, he assigned me numerous musical tasks which readers might find surprising. Most Americans, including me, went to Paris to play his pieces or those of Franck's, not to begin lessons on Couperin, Grigny or Bach "Orgelbuchlein." I had prepared Franck and Langlais, of course, but having played those, he demanded I play an entire Mass of Couperin, much of the Bach Orgelbuchlein and at least some Grigny and Dandrieu, before going to other pieces I had learned my first year at TCU. I have markings and notes about style, consistent with what became "de rigeur" later in the U.S. in what would be known as the "early music movement.'" We think of Marchal (and later, M-C Alain) as having championed early music, but my experience that summer opened the world of performance practice for me, studying with Langlais.  Lesson at 26 rue Duroc Schwenkedel organ Lesson at 26 rue Duroc Schwenkedel organ It would dawn on me much later that earlier music was still revered and taught straight through the 19th century, with new editions and traditions remaining hot topics evolving through the turn of the century with the "organ reform movement." After all, Tournemire had enlarged the beautiful Cavaillé-Coll instrument Franck played and loved for the expressed purpose of playing earlier music, exploring the "colors" of stops lost through organ building in the previous century, as beautiful as they were. But that's a whole other topic, on which I wrote a dissertation. The Schola Cantorum, where I would study on a Fulbright Scholarship in 1968-1969, was busy retaining the Franck style, but also publishing scholarly treatises and music from earliest times in the Notre-Dame School through the 18th century masterpieces we now have come to know and cherish. Improvisation remained front and center in the teaching of all professors who taught at the Schola, taking the example of Franck, and making it a priority right through the hundred years to the teaching of Langlais. The School for the Blind (Vallentin Haüy, Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles) also had acquired treatises and manuscripts in Braille which Langlais and other blind students were encouraged to read and know. Langlais told me that he "had read all the primary sources from the 18th c.," and knew about articulation, ornamentation, over-dotting and registration practice for organs such as the one at St. Gervais, still then in its original temperament (Mean-tone), the organ played for a century by members of the Couperin family. He took all of us in the Texas group to St. Gervais, where we could play the organ and hear about the traditions associated with the Couperin family. It was, sadly, in need of repair, but in 1964, it was playable enough that I could hear the temperament, completely new to me, marvel at the stubs for pedals and dream of what it must have sounded like in the centuries before. Not long after that, I visited Poitiers! It would prepare me for a lifetime of living with Meantone. The following is an example of the articulations Maitre Langlais taught me as I prepared to play the "Dialogue sur les Grands jeux" from Messe pour les Paroisses by Francois Couperin for the Postlude of High Mass on July 5, 1964, at Ste. Clotilde….my "coming out!" Langlais taught that there were three kinds of touch, or what we call articulation: legato, portato, and staccato. Legato was assumed unless playing earlier music (Couperin, Bach, Grigny), in which case, portato was always desired. Portato could and should be of varying lengths, not half-value. Notes on strong beats would take precedence, using agogic accents by delaying the attack and by giving the note a bit more length. Inégale, Langlais taught, was not always obligatory, but rather in the realm of personal taste: how much to apply on 8th notes moving step-wise. The registrations were always of great importance to him. I wrote down by hand as he dictated the stop-lists of many 18th c. organs, including those Bach knew at St. Thomas in Leipzig, those of Couperin, and the extensive list for the organ at the School for the Blind, originally a Cavaillé-Coll, enlarged by Gonzalez with mutations and stops of color in order to play early music. At the time, I didn't think much about it, as I thought that, though curious and historically "interesting," the musical foundation Langlais was requiring of me was not where the organ profession was going. The organ reform movement had just celebrated its beginnings in Albany, TX, with the installation of a large tracker, built by Otto Hoffman, Dirk Flentrop, and Joseph Blanton, with advice from Donald Willing, which in turn inspired in Dallas, in a futuristic church influenced by Corbusier's Ronchamp, in France, St. Stephen Methodist in Mesquite, TX, the first tracker by a group of builders, Robert Sipe, Rodney Yarbrough, with help from George Bozeman, Roy Redman, among others, who would enter the field with their own companies. Other Flentrop instruments and American built organs by Charlie Fisk, then John Brombaugh, followed in the Northeast. I attended the historic dedicatory recitals of these Texas installations in Albany and Dallas as they were put through their paces. I still remember the recitals of Donald Willing, from the U. of North Texas playing in Albany, and Robert Anderson, from SMU, dedicating the Sipe-Yarbrough organ in Mesquite, 1962. Both organs still serve their congregations well. Concerts are still played on both. Again, I digress. I didn't know then that I would, a few years later, travel to the French Pyrenees, the Mountains of Catalonia, where I would create music for a Troupe de Theatre, Avant-Quart. In doing so, I would use an electronic harpsichord for 16th c. plays by Molière and a portative organ built by Claude Armand, loaned for earlier plays and concertizing. I would research and perform indigenous music by the Troubadours, invite musicians who played the lute, violas da gamba, Baroque oboe, flute, and with singers offer concerts in the Cathar chateau, Puivert, where the Troupe organized three years of Festivals and touring concerts between 1969 and 1971. Heads of "les Troubadours" from the Middle Ages, playing portative organs, vielles, cornemuses, lyres and cornets look down from their 12th c. cornices carved in stone telling their story to this day. It was the only chateau among the many, including Monségur, used only for the arts, not for war. I digress. Meanwhile, I was hopeful for a scholarship to Eastman, which didn't come for another year. I stayed with the Troupe until that word came from Eastman that I could receive the scholarship with the assignment of work with the Collegium Musicum, coaching the singers (mostly hopeful operatic vocal students with heavy vibratos) and playing harpsichord, copying music, living in the early music stacks of Eastman's Sibley library. The dye was cast. I would pursue early music, performance practice, co-found the Texas Baroque Ensemble with my soon-to-be husband who played the gamba, Dr. Charles Lang, direct the Early Music Weekends at Round Top, TX, and eventually retire to establish the Big Moose Bach Fest and the non-profit Music in the Great North Woods of Northern New Hampshire. I blame, no, credit, Jean Langlais and the Schola Cantorum for all of that. In future posts I will write more stories about my 10 years with Langlais, about the honor of guiding him on his American tour of '67 during which time he turned 60 on February 15th. There are stories to tell about his trips to Boystown, near Omaha, my lessons during the Fulbright Scholarship year, learning to improvise at the Schola Cantorum, taking lessons on his home organ, a neo-Baroque organ by the Alsacien, Curt Schwenkedel, attending with him the funeral of Jeanne Demessieux, taking lessons and recording with him at Ste. Clotilde, his receiving the Legion of Honor, at which occasion he improvised with his dear friend, Olivier Messiaen, our travels throughout Brittany, the Southwest of France, the Pyrenees, and aboard the beautiful ship, La France. The "great musicians" learn from "the greats," who in turn learn the lessons of "the greats" before them. Jean Langlais, my teacher, my friend, was one of the "greats." The gifts he gave me were many, treasured, undeserved, and "great!" To follow my blog: https://susanferre.weebly.com/blog

To order the CD "Hommage A Jean Langlais," Three improvisations by Langlais with additional works of Langlais played by Ferré, order through https://www.susanferre.weebly.com

0 Comments

|

Susan FerréGood Times Book Archives

June 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed