|

In the summer of 1964, after my Freshman year of organ study with Emmet Smith at Texas Christian University who had spent time in Paris studying with Rolande Falcinelli (a protégé of Dupré's), Emmet announced a summer trip back to Paris for further study and to tour organs in Europe more broadly (Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and places in between). As I could not afford the expense of the entire trip, we planned that I would join the tour, taking the beautiful ship, La France, for the first sessions in Paris with the eight member group, remaining in Paris by myself for the next six weeks, joining the tour for the passage back to New York.

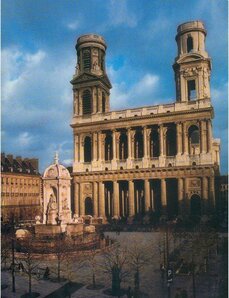

Our first group session with Dupré at his residence in Meudon was memorable. He greeted us warmly and welcomed us in his music room, a room he had had constructed in order to work at his own pace, "in peace." He explained to us that as fortune would have it, his home was located only a short distance "across the alley" from the former home of Guilmant, where he had spent so many years in lessons. When he learned that Guilmant's family had decided to sell the magnificent Cavaillé-Coll organ, he jumped at the chance to finish his "salle d'orgue" in order to acquire and install the beautiful, organ which he felt so privileged to acquire from his mentor's descendants. When at last we were invited to play this magnificent organ, we were, or at least I was, petrified with what seemed to be a spiritual encounter with an instrument which had served so many talented hands and feet. I don't recall who played first, but knowing that I had spent my freshman year with Dupré scores and methods, my teacher having taught these precepts enthusiastically, it did not occur to me that, if we played the notes accurately, there would be much left to discuss or criticize. I was correct. Dupré was perhaps just being kind and polite toward Americans, even Texans, who had not learned to improvise or play without scores, due to our lack of training in composition or theory, and reflecting our naïveté in these matters. Nevertheless, he seemed complimented that we had come to seek his opinion in playing Bach, Franck, Gigout, Widor and whatever else we had brought. I was armed with my Dupré editions of Franck and Bach, and no doubt ventured to play Cantabilé and Pièce Héroïque, followed by the G Major Prelude and Fugue of Bach. I had also learned his G minor Prelude and Fugue, which I may have played at a later time when I returned a few years later for private instruction. "Très bien, mon enfant," he responded warmly, after which he ventured into stories about his trips to America. He invited us to join him in the loft at St. Sulpice, which we did, and which I continued to do in the years following. During those later years, between 1968 and 1969 when I was in Paris studying with Jean Langlais, a year after serving as Langlais' guide on his '67 American tour, and in the few years following, I found myself attending weekly masses at St. Sulpice. The Sunday schedule was such that I could attend the 9:30 am Mass at Ste. Clotilde, rush over to St. Sulpice, sometimes joining Dupré in the organ loft, but more often than not, just listening from down below, before taking the Metro to La Trinité where I could hear Messiaen's improvisations during the 1:00 pm Mass. I had also been given time at St. Sulpice during the week for practice in the side Chapel. I was forever grateful, and again, warmly encouraged and received by the sacristan. It was Langlais who, perhaps timidly, or perhaps to show off one of his American students to his former professor, sent me to study further with Dupré in the summer of 1969. Langlais had also arranged lessons and concerts for me with Litaize, Messiaen and Duruflé. I recall that Langlais cleared the way for me by calling the Dupré residence, and I followed up with my own call to arrange a weekly time to play for the now visibly aging master. I played for the first few lessons, works by Widor (Symphonies 5 and 6), Vierne, and Dupré, of course, all of which I had previously played for Langlais. All went smoothly. He seemed impressed, or was he just being polite and kind, again? He pretended to remember that I had been there some years earlier, with a group from Texas. For the 4th lesson he asked that I bring Bach. Having grown up with his method in lessons with Mr. Smith, and having heard Dupré play Bach so many times at St. Sulpice, I knew not to play too fast, nor to infuse anything but agogic accents, to control my playing so that the power of the work itself would take center stage. I was quiet, keeping knees together, moving as little as possible. He was, in fact, now clearly delighted, and proceeded to tell me stories of his lessons with Guilmant, his lunches with Widor, his love of teaching, how his "salle d'orgue" had been bombed during the 2nd World War, and even about relationships which dated back to Glazunov, Liszt and Chopin. I remember feeling a sense of relief. I delighted in his stories. That was short-lived because he then insisted that he wanted to hear me play Franck! Oh DEAR! I knew, having studied years with Langlais at that point, that playing Franck would be out of the question. Langlais and others in the Franck school had insisted that Dupré, perhaps unwittingly, but indeed vigorously, with his publications of the "corrected" Franck editions, had "changed EVERYTHING!" I was taught that Dupré had imposed his own method, which had been derived from Guilmant, who in turn had been influenced by Widor, Lemmens, Hesse, Rinck and Kittel, and who had played Franck during his tenure in Franck's class in his own "unique" style. The story was told to me by Langlais that Franck was so humbled and honored by Guilmant's playing of his (Franck's) works, that he said nothing negative about the "unique" style with which Guilmant played them. Meanwhile, the students in Franck's class, who felt inspired by Franck's teaching, his improvisations and expressive playing, held firmly to the traditions with which Franck himself played. Franck's own students maintained, upon hearing Guilmant's performances of Franck's works, that Franck himself, though surprised, was complimented that his works would be played at all, and never insisted on his own interpretive style from his students. In any case, I had understood that the editions by Durand were the only editions corrected by Franck himself, and I had long since put away my Dupré editions. Having lived with the organ at Ste. Clotilde for years at this point, I knew that I would not fare well if I tried to play Franck in the style to which I had become accustomed, hearing Langlais, specifically, but others too, play Franck's works at Ste. Clotilde week after week. This is a much longer story, but to finish the point about playing for Dupré, I made up an excuse not to return for lessons… something about moving to the Pyrenees, or moving back to the United States… something like that. He was most gracious and wrote a note which he handed me, in case I needed to prove that I had actually studied with him. It stated that I "had made good progress" under his tutelage. That was that. Reflecting on those times and interactions, I remember being moved to tears while listening to Dupré play Bach at St. Sulpice. His tempi, which at first I found slow and ponderous, gathered immense intention and weight as they progressed to such grand conclusions that I was completely overwhelmed. To hear him improvise fugues and contrapuntal pieces, as if they had been previously written, was to wonder if I would ever again hear such a grand talent in my lifetime. The silence which followed his fugal postludes, whether Bach or improvised, was deafening. Many just sat in stunned silence. I never wanted to say anything to him as he departed quietly walking out of the church with his briefcase in hand. |

Susan FerréGood Times Book Archives

June 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed