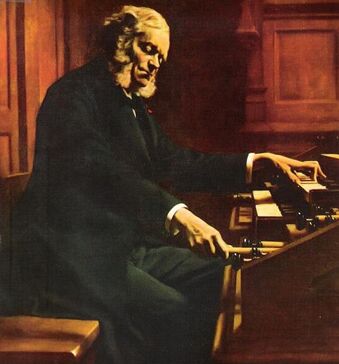

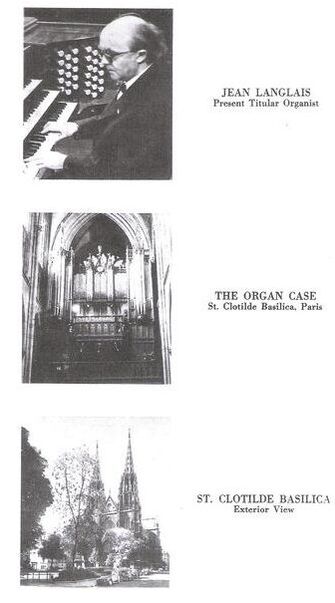

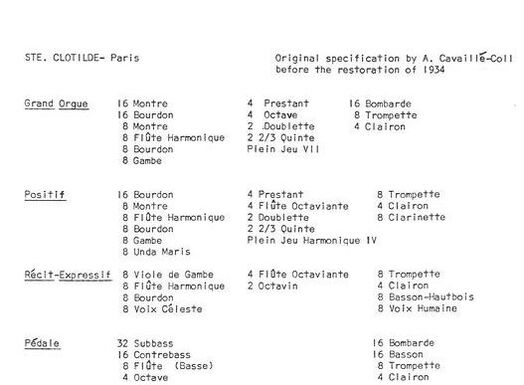

by Susan Ferré A scholar, I am not. But I read a lot and try to keep up, and I've had some important teachers. I'm a story-teller. I believe that oral history is at least as important as scholarly, written history. I have a story to tell about being one of many inheritors of the so-called Franck style and what has become known as "the Ste. Clotilde tradition." My scores are heavily marked from my time in France, especially the years between 1964 and 1969. The sound of the Ste. Clotilde organ still rings in my head. I've not heard anything like it since. At the time, I compared what I was learning from my teacher, Jean Langlais, with others who were studying with Maurice Duruflé and M-C Alain. The consistency was obvious. YES, there is a Franck style, a Ste. Clotilde tradition, changes in the organ, and recent scholarship, not withstanding! While studying in the summer of '69 with Dupré, I declined to play Franck for him, even though I had begun organ study playing Franck using Dupré's editions. "Oh, NO!" my Maitre, Jean Langlais, would say, "He changed EVERYTHING!" I'm aware of hotly debated articles now concerning changes to the organ at Ste. Clotilde. Franck's own kind attitude toward Guilmant's "different" interpretations, that "other" school of playing Franck's works, and so forth, are well documented. In spite of the fact that no two students play exactly alike, and varying tempi are heard in historic recordings leading some to contend that "no one can prove much of anything about the style," why would we care how Franck played? I'm guessing that because you are here, you are interested to hear what some of us learned and why we hold to a "tradition" which derives from the composer, a tradition which attempts to become close to the composer's intent. It's the same reasoning we use today doing early music. The more we know, the better the result, or at least the closer we come to inspiring an audience. The problem, which Jesse Eschbach in a recent article in TAO calls a "war" between the two camps, stems from the Lemmons/Hesse/Rinck/Bach line through Guilmant, Widor and Dupré, which creates the opening, culturally and musically, for the German orthodoxy once again to reign with impunity over what was typically "French." So prevalent was the revisionist thinking in Paris about Franck that Vincent d'Indy created the Schola Cantorum, where I studied, in order "to preserve Franck's own style," a style Franck himself was too modest to promote, according to his students and followers, and a style rooted in early music history, improvisation, sincerity and lyricism...not to mention power and beauty. The French attitude is perhaps more existential and experiential than scholarly, the traditions taught carefully, transmitted directly from teacher to student, many of whom put their thoughts in writing: Vincent d'Indy, Charles Tournemire, Louis Vierne and many others. History is often determined by those who have opinions and systematically write them down. What composer wouldn't want their artistry to be traced back to Bach? Still, while in France over a ten-year period I never sensed a "war" between musical factions or traditions. It was Langlais, after all, who sent me to Dupré, who had been one of his teachers. Teachers of Jean Langlais included three of Franck's pupils, Albert Mahaut, Adolphe Marty (teacher at the School for the Blind for many years) and Charles Tournemire. All adhered to and admired the expressive playing of their teacher, César Franck. When Alexandre Guilmant played Franck's music in public, Franck was humbled by the "creative and innovative" way his music was played, and said nothing negative to anyone about it, although others remarked how Guilmant's style was different and personal, not respectful of their Master. Maurice Duruflé also studied with three of Franck's students, including Vierne and Tournemire. The style as passed on by both Langlais and Duruflé also matched the teachings of Marie-Claire Alain, a close family friend. In addition, now we have recordings which abound and much detailed research by Rollin Smith, Robert Sutherland Lord, who coined the phrase "The Ste. Clotilde Tradition," Lawrence Archbold and William Peterson, hundreds of students and composers of stature: George Baker, Naji Hakim, David Briggs, and professors Russell Saunders, Robert Glasgow, Ann Labounsky, Karen Hastings, Marie-Louise Jaquet-Langlais (a classmate of mine at the Schola Cantorum), and others noted on the extensive, annotated bibliography compiled by Ann Labounsky. Here the question of common notes arises: "Tie common notes if the second note is not part of the melody. This makes for a smoother result." Breaks between phrases and in some sequential patterns may be added, as in Cantabile. Tempos must be broad, but never sluggish or dull. The overall tempo must remain the same, but it must move forward when the music does to create great energy, and pull back just as much at the points of relaxation. Certainly there should never be a sudden accelerando, stringendo, or race to the finish line, as is often heard by many virtuoso players. The tempo can be relaxed before the entrance of a theme, especially if preceded on the first beat by a rest. (Example: Pièce Héroïque... to quote M-C Alain: "The train does not leave the station at 60 miles an hour." Duruflé also used to say this.) Other stressed notes: 1) top notes of appoggiaturas; 2) the first of two repeated notes, even if the first in on a weak beat; 3) notes held back before a sudden dynamic change; 4) off-beat notes after ties, when one prolongs the dissonance, as in all French music up to this time; 5) upward resolving suspensions or retardations; 6) penultimate notes and chords, delaying the final chord. The subject of articulation never came up with me when playing Franck's music. Langlais taught that there were three kinds: legato, portato, and staccato. Legato was assumed unless playing earlier music (Couperin, Bach, Grigny), in which case, portato was always desired. Portato could and should be of varying lengths, not half-value. Staccato had many varieties. Dupré's half-value, or at least heavy weight, was different from the short, crisp, hot-potato approach of Guillou, for instance. For Franck, also a pianist, as was everyone who played the organ, legato was the beautiful, expressive means by which he played the organ freely. Legato has become another hot topic. Summing up, it IS possible and even preferable to exercise musicality and self-expression within the framework of an authentic "Franck" style: enlarge rests, hold long notes more than their value in a series of three, with more and more emphasis on the highest note, the top note or penultimate in a long phrase. Be aware of canons and choral themes. Create space between sections. Overall tempi should not be too slow. This is spacious music. Even without good acoustics in American churches, one can pretend to be at Ste. Clotilde, or at any other beautifully voiced Cavaillé-Coll instrument.  The photos above date from 1964 The photos above date from 1964 Final thoughts anticipating questions: 1) Question: Do I think that the penciled-in metronome markings, ostensibly in Franck's handwriting, mean that we should play his works much faster, even twice as fast in some cases,as the "Tradition" suggests? Response: No, for many reasons. I can imagine an editor asking for metronome markings, which I know Langlais and other composes despised, especially those who play freely, and responding with distain. Langlais did not like them, and famously championed expressive playing: "You must play this VERY FREELY, exactly like this!" "But the metronome markings...?" "Not important! ...exactly like THIS!" 2) Question: What about "ordinary touch," since Franck was a fine pianist, with very large hands? Did he play with pianistic technique at the organ? Response: Franck had an octave and a fifth, as did Dupré, but didn't mind adjusting the notes to fit one's hand. Langlais' hand was smaller: an octave and a third. There are multiple solutions to this problem and apparently Franck didn't mind "adjustments" of this kind. Students of the "Tradition" were familiar with how to play smoothly, using finger substitution, thumb glissandos and other tricks in order to achieve a smooth legato. Legato was assumed and part of the style. Just because Franck also played the piano beautifully, didn't mean that he used the same articulation at the organ, just as we all make that differentiation today. Even playing original C-C organs (another workshop altogether), achieving a beautiful legato is not difficult. Liszt's piano technique, still taught at the Liszt Academy in Budapest, is a case in point, but for another discussion, as is the talk about C-C and his evolution in organ building. 3) Question: How "authentic" does one have to be? If there is a "war" on, which tradition should I choose? Response: As passionate as I may feel concerning the authenticity of the Franck style, I recognize that Franck himself did not agonize over such questions. He played from the heart, and a player today must follow their own muse. This quote from R. J. Stove's book on Franck ends with the perfect response: "It would be a foolhardy music lover who preferred any of these approaches to the others in every circumstance. A much greater temptation is to imitate the proverbial donkey who starved when forced to choose between equally delectable bales of hay."

0 Comments

|

Susan FerréGood Times Book Archives

June 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed